Given that we are approaching two full decades of ongoing panic—shading by this point into grim resignation—regarding the dominance of remakes, reboots, and “IP films” in Hollywood, there was something striking about the collective online response to the announcement that Spike Lee was remaking Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963). In my particular corner of Twitter and my particular cross-section of the cinephile/critic community there was essentially no response but excitement, breathless speculation about what Spike and Denzel would bring to this material, exhilaration at the prospect of a fifth collaboration from these two masters who each bring out one another’s best work. It was a reminder, perhaps, that the objection has never been to remakes per se—that is, to the artistic project of revisiting or riffing on an existing work—but rather to the cynical Hollywood machine which sees name recognition as the industry’s most controllable commodity, a way of selling movies without the messiness of collaboration with actual artists, something bankable that you can really own. Or maybe it was simply a reminder that the people really love Spike Lee, that this is an artist of the stature to say “I’m remaking one of Akira Kurosawa’s best films” and generate only feverish anticipation, that we are thrilled by virtually any project from a master filmmaker with something left to say.

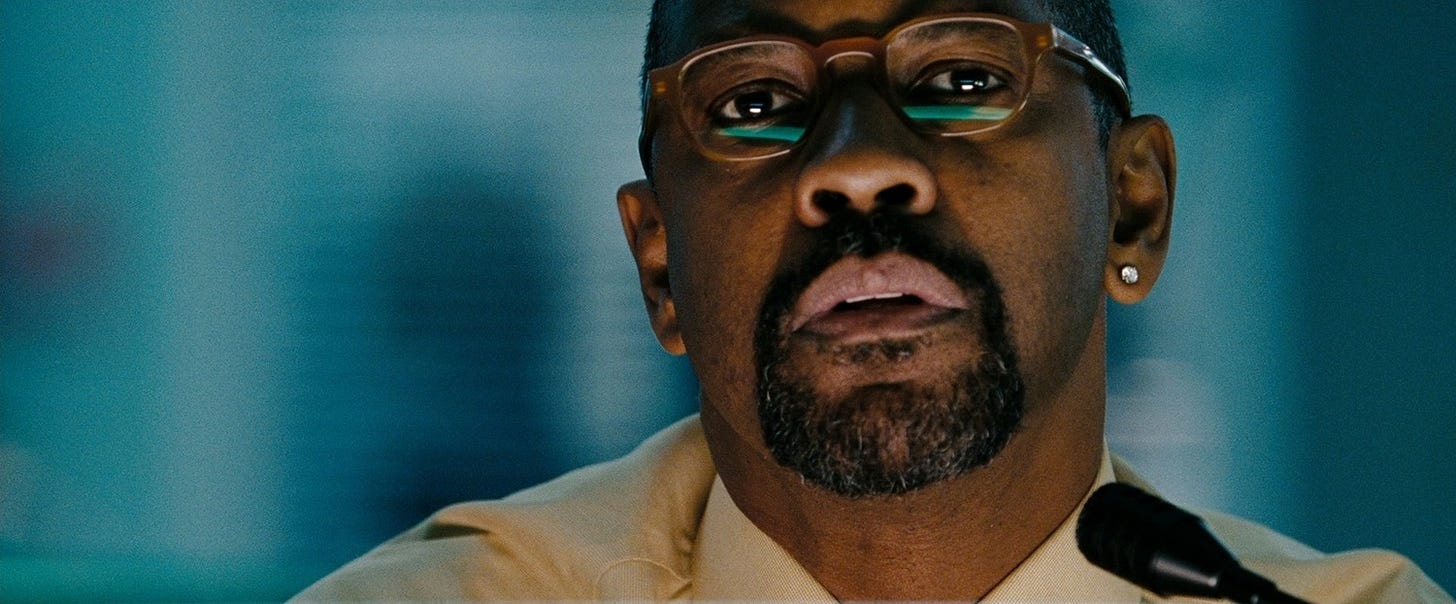

As it happens I absolutely loved Highest 2 Lowest, a stylistically electric and pleasingly thorny outing from a filmmaker clearly grappling with his own age and his growing distance from modern cultures of creation. Like most late Spike works it’s firmly idiosyncratic, occasionally messy, but it’s also thrillingly personal, a film that looks squarely at the reality of becoming a rich Black artist, the way wealth and age complicate relationships with radical creativity and ‘authenticity’, the way class and capital impose hard limits on the liberatory potential of Black success. It sets its sights on the New York City of the penthouse set and finds it sleek and sterile, festooned with the signifiers of culture and history but unable to truly make sense of them. It poses hard questions to which Spike himself, clearly not wholly uncompromised by wealth and myopia, has no easy answers. (There’s a piece to be written, I think, placing Highest 2 Lowest alongside Sinners, which takes a much different and more didactic, though not uncomplicated, approach to the question of Black commercial and creative ‘success’.) And of course it provides a genuinely outrageous showcase for Denzel, who has never been less than great in a film and is transcendent here, effortlessly in step with the film’s off-kilter rhythms, finding the magnetism and the pride and the ugliness in a character who (notably unlike Toshiro Mifune in High and Low) appears in virtually every scene. For my money it amply rewards the excitement that greeted its announcement, and vindicates our collective instinct that this material drew Spike for all the right reasons.

It also reminds me strongly of another project from Denzel Washington and one of his most important career collaborators, another movie with 21st-century New York squarely on its mind, another remake of a beloved earlier masterpiece. I’m thinking of Tony Scott’s The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009), the fourth of Denzel’s five films with Scott, a figure matched (thus far) only by Lee and Antoine Fuqua. I was not dialed into any kind of online film discourse when this film was released, but I remember the contemporary critical response, which was tepid; the Hollywood remake machine was by this point beginning to really hum, and critics were quick to register their dissatisfaction with it, and to compare its products unfavorably with their canonized originals. (We might note for instance some of the era’s many horror remakes, virtually all scorned on release, several undeservedly.) The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974) might not be High and Low, but it’s a rightfully beloved Swiss-watch thriller, anchored by a pair of terrific performances and a preponderance of dirty old New York flavor. Tony Scott was not, in his lifetime, widely regarded as the kind of filmmaker whose projects deserved to be assessed as art, and his Pelham remake was generally dismissed as entertaining hack-work. In my view, however—and I’m glad this no longer feels like as outré a take as once it did—Tony Scott was a brilliant director, whose frenetic late style constituted a genuinely bold experiment in blockbuster filmmaking, and The Taking of Pelham 123 is much better than its reputation, a stylish showcase for Denzel’s gifts and a clever update for a twenty-first century NYC. It may not be Highest 2 Lowest, either, but the parallels are there, and it deserves renewed attention in its own right.

Its distinctive style is something The Taking of Pelham 123 announces from its earliest moments. Critics were not always receptive to the aggressive rhythms and smears of color that characterized Tony Scott’s 21st-century output, and in this respect Pelham 123 does itself no favors by opening with a remarkable but abrasive opening credits sequence set to arrhythmic snatches of “99 Problems.” In truth, however, this is an exceptionally assured film, just as comfortable with more measured compositions and richer colors as with the pugnacious style of its more heightened moments. Scott was always a master of space and its logics, from the submarine interior of Crimson Tide (1995) to the hurtling trajectory of Unstoppable (2010), and the physical subway tunnels where most of the “real” action takes place are always interrelated smoothly with the MTA head office and its vast interactive readout. In his Enemy of the State (1999) Scott pioneered a visual language of mass surveillance precociously suited to the post-9/11 world, and there is something of this in Pelham 123 as well, a sense that from their windowless downtown office the MTA higher-ups have a subterranean world at their fingertips, not to mention the fact (prominent but perhaps narratively underdeveloped) that the whole hijacking is captured on and off by a laptop webcam. The editing here by longtime Scott collaborator Chris Lebenzon is rapid but not generally frantic—the abrasive style of those opening credits recurs only infrequently—and to the extent that it is, it’s purposeful, reflecting a scenario developing at unmanageable speeds and threatening at every moment to careen completely out of control. Scott’s late style may have been aggressive, but it was built on the cleaner formalism of his earlier works, and Pelham 123 finds it very much always under his control.

That opening credits sequence serves also to introduce John Travolta’s villain, ‘Ryder’ (get it?), one of the film’s most notable departures from its source material. Robert Shaw’s Mr. Blue was a classic villain of the icily competent type, a steely-eyed professional with a patrician distaste for his more volatile subordinates. Ryder, by contrast, seems like kind of a coked-up shithead, possibly more impulsive than some of the dull-eyed killers on his crew, certainly prone to shrieking orders and barking out obscenities. Travolta was in a somewhat eclectic stage of his revived post-Pulp Fiction career by this point, and brings a great dickish energy to the character, but to a viewer expecting the machinelike cool of Robert Shaw Ryder must have come as something of a disappointment. In my view, however, one of the film’s cleverest choices is to subvert our expectations for this kind of heist-movie villain. At one point Denzel Washington’s Walter Garber fumblingly asks Ryder “are you…terrorists or something?” and Travolta’s snapped “do I sound like a fucking terrorist?” feels like a winking reference to Die Hard’s Hans Gruber, whose supposed geopolitical aims are simply a devious smokescreen for his purely financial ones. Ryder, too, turns out to have a plan beneath the plan, and just like Gruber’s it turns out to involve the response to the crime itself: what Ryder is running is less a heist than an insider trade, an attempt to capitalize on the market upheaval that a subway hijacking will cause once it becomes public. He seems like kind of a coked-up shithead because that’s exactly what he is, a stockbroker turned felon, the kind of guy who gives himself away by revealing that he once flew an ass model to Reykjavik. This is a master criminal for 21st-century New York, a Wall Street prick willing to kill to raise the price of gold, a man who understands that the crime itself matters less than how it will play on cable news.

A Wall Street avatar like Ryder was a figure with a particular cultural and political valence in 2009, with the global financial crisis of the previous year still sending shockwaves through American social and economic life. There must surely have been very few historical moments at which audiences were more primed to feel contempt for guys like Ryder, authors of a world-historic economic collapse; in Ryder’s total lack of consideration for the lives of his hostages, his visible thrill at the bet of a lifetime, it is hard not to see the amoral gamblers of the shareholder class, who have never really cared that they are playing with people’s homes, people’s savings, people’s lives. Ryder himself has just finished a ten-year prison sentence for financial crimes, and in June 2009 it was perhaps just possible to imagine that such a fate still lay in store for the architects of the 2008 crash, that there existed something like accountability for people who pursued their own profits at the cost of unfathomable ruin. Ryder’s gamble itself, however, told the real story. This is a system where a train full of dead hostages can make someone a lot of money, so long as they’ve got a lot of money already, so long as they know which buttons to press. The lopsided “recovery” from 2008, since mirrored by robust market performances in the wake of COVID-19, sent out the message in no uncertain terms that Wall Street’s interests are not everybody’s interests, that the line can still go up with the world on fire. Ryder makes his money whether the hostages survive or not; people like him know they’re always the house, and the house always finds a way to win.

The figure who provides the key break in the search for Ryder’s identity is none other than the mayor of New York, played with weary petulance by James Gandolfini in one of a handful of major post-Sopranos roles. There is clearly supposed to be at least a little of Michael Bloomberg in his character, a multimillionaire who waives his mayoral salary, and in this respect it’s notable that he’s depicted as cynical, whiny, and effete. In another clever flourish from screenwriter Brian Helgeland, we first meet the mayor on the train, which he seems to ride to work every day as a naked publicity stunt, and which he absolutely cannot stand. It’s easy to imagine a still perfectly watchable but much stupider version of this movie, in which this mayor creates the kind of nuisance that actively worsens the hostage situation; instead, with his background and knowledge of Wall Street types, he’s the man who successfully intuits Ryder’s backstory from hints dropped to Garber. In this film not everyone who’s kind of a sleaze is worthless, and a flawed, venal mayor can nonetheless help the city. At the end of the film he makes a speech to Garber thanking him for “going to bat for New York,” and we can see he means it, despite his frank admission that the job of mayor usually finds him thanking people he doesn’t know for things he doesn’t care about. Garber asks him if he’s a Yankee fan and he replies “no, not really—I mean, yes, of course,” as though to a nearby news camera, a moment of playful self-awareness from a character the film seems to regard, on balance, with some affection. In the film’s lexicon he represents a certain kind of wealthy New Yorker: compromised by capital, maybe, and a little self-obsessed, but fundamentally still part of a city that sticks together.

And then, of course, there’s Garber himself, Denzel Washington’s harried train dispatcher, representative of a very different kind of New York life. He’s an MTA lifer, having worked his way from maintenance to conductor to motorman to dispatcher and now, finally, to an executive position from which he has, at the start of the film, been mysteriously suspended. Everything is set up here for an uncomplicated ode to the MTA’s working stiffs, the guys who know trains and love them and put in the years; Garber is the kind of pro who can be years out of a dispatch job and still step back into it like he never left, an effortless wrangler of this vast and many-headed beast, a tireless servant of the city. This seems like the kind of charismatic everyman Denzel can play in his sleep, and we’ll thrill to see him do it, confident that he doesn’t need much depth on the page to put in precise, compelling work. He’s as good an anchor as one can imagine for a morally uncomplicated two-hander in which we’re always pretty sure we know the score.

The Taking of Pelham 123, however, has something more interesting to offer than complete moral simplicity. Garber has a secret of his own, revealed around the film’s midpoint in by far its finest scene: he hasn’t been unjustly suspended, because he did take a bribe, from a Japanese train manufacturer competing for an MTA contract. Denzel’s work in this scene is beyond remarkable, far better watched than described; in the space of seconds he drains Garber of all his dignity, a perfect note of petulance entering his voice as he protests his innocence, followed by absolute weariness after he confesses in a panic to save the life of a hostage. He insists he took money from the company whose train was genuinely better; he says he used the cash to help put his kids through college; as he talks about his children his voice breaks, his eyes water. But he took the bribe, and now everybody knows it. It’s almost impossible to imagine another actor conveying this sequence of emotions with the precision Washington manages here, and without inducing whiplash; the whole exchange lasts just two minutes, the film’s most important character moment over almost as soon as it begins. Ryder, carried away by a feeling of kinship with Garber, a sense of shared grievance, accuses the MTA bosses of trying to humiliate him, but Garber, sounding utterly and elementally defeated, demurs. “No, no,” he says, all his petulance and desperation gone. “No. I did what I did, and, y’know…it’s not the MTA’s fault.” He’s expressing a sincere feeling, but he’s also rejecting the opportunity to bond with Ryder, whom we are invited to recognize even at Garber’s lowest moment as a far worse kind of creature, a would-be robber baron who will never spend a dime on anybody else. It's another place where The Taking of Pelham 123 avoids the path of least resistance, opting instead to argue again that flawed but decent people make the city work. It takes a character Denzel could play on autopilot and creates something genuinely worthy of his gifts.

The film, too, is worthy, for all that it’s a remake, for all that Tony Scott’s authorial imprimatur never quite equaled Spike Lee’s. It’s a film Scott and his collaborators craft with distinct and considerable style, an immaculately paced thriller, a genuine showcase for the greatest actor of his generation. It’s not the same as its 1974 predecessor, but it never could have been; the movies have changed too much, and so has the city. Highest 2 Lowest could never have been a film about the hierarchies emerging from Japanese postwar industrial recovery, and The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009) could never have been a film about the New York of the 1970s, a city transformed in the intervening decades by soaring rents, by various metastatic financial and racial inequalities, by Wall Street guys like Ryder and the high-stakes games they play, by 9/11 and the American security state. Tony Scott, who adapted his formally rich and adventurous cinema to a Hollywood future which he saw better than Hollywood, delivered a clever, propulsive update of a classic film story, a vivid snapshot of a particular moment in American economic and cultural life. If we’d been more alert at the time to his particular gifts, we might have celebrated this impulse then the way we do now.

Outstanding writing, especially on Scott's remake. A maligned film I can only fall in love with.