The Tell of Us All

History and the World of Mad Max

Spoilers follow freely for all five Mad Max films.

It starts small, as these things always do; a single war-band, a gang, if you will, drawn together the way gangs always are, by charisma and fellow-feeling and perhaps the threat of force. Then comes a larger gang, a confederation of gangs, perhaps, each with their own leaders and their own interests, held together by a big boss for as long as he can. A town emerges, a place to gather and trade, and here too there is a boss, who promises orderly business and relative peace. But her power is not absolute, nor is that of the warlord who rules a sprawling kingdom; it rests on consensus and coercion and negotiation, on the cooperation or subjugation of rival powers, on supply lines, on work and blood and engine oil.

In a loose, simplistic way, the narrative sketch above takes us through George Miller’s Mad Max films in order, from the motorcycle gang of Mad Max (1979) to the Wasteland kingdom of Immortan Joe in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024). It makes a convenient picture, as the complexity of Miller’s future societies increases with the budget and ambition of his films. This progression through social forms, however, also reflects something essential about the world of Mad Max: the smaller, simpler formations of the early films are also the building blocks of the broader Wasteland, and their early interactions with Miller’s first titular hero introduce, in miniature, the series’ rich and sophisticated arguments about how social forces interact and drive human history. History, to a significant extent, is what the Mad Max series is all about; history both as a process, and a story we tell ourselves about the way things have come to be.

A Purposeful Savagery

For all their outlandish qualities, all the imaginative visual and conceptual work of Miller and his collaborators, none of the basic social formations we meet in the Wasteland are unique products of it; human history, particularly the history of premodernity, is littered with scavengers and traders, warlords and war-boys. In encountering this past for the first time, beginning students of history sometimes find themselves groping around the edges of a question almost too vast to confront, a question they begin to realize—as they articulate it—might be the question, the question that comes before all the rest: how does the world come to be unequal? How does such a small slice of humanity convince the others to give them everything, to create and re-create, with each new generation, a world which grinds so many to dust for the benefit of so few?

The systems and structures which create this world in our own day efface themselves, make themselves seem natural, endless, as such systems always have. The original Mad Max (1979), cleverly situated just a few years after the ‘present’, creates a world in which these systems are still visible, however fragile and absurd; there are still cops, however brutish and anarchic their methods of enforcement, and courts of law, however much the Halls of Justice might resemble a crude prison or insane asylum. The property order preserved by these systems is tottering but intact; this is still a land of shops and single-family homes, however ominously menaced by the likes of the Toecutter, soon to inherit the earth. Mad Max 2 (1981), by contrast, brings us to a world where these systems have collapsed utterly, at least in the vast Wasteland which will be our home for the rest of the series. The civilizational slate is now very nearly blank, and Miller invites us to watch what emerges to fill the vacuum, to see what structures humans build (almost, though crucially not quite) from scratch. In this respect it offers striking if general parallels to the premodern, the ancient, even the neolithic; the very first moments in which small subsets of humanity emerged as lords of the rest. In those very first stirrings of human hierarchy we confront the formerly invisible and find it inescapable, the great mystery who takes, and how suddenly filling the field of our historical vision. It fills, too, the field of Miller’s narrative vision; the rest of the Mad Max series is suffused with it, with questions of power, and production, and the “purposeful savagery” of industrial civilization.

This is an explicitly materialist framing, one which centers the realities of production and their various externalities. But the world of Mad Max makes this mode of analysis hard to resist; from its earliest chapters Miller’s world is a world defined by resources, the things people need, the things that make the world run. This is not as obvious a choice as it might seem at a glance. Scarcity is a standard feature of post-apocalyptic narratives, of course, but Miller is unusually attuned to how scarcity relates to society’s complex and interconnected material functions; it appears to be the disruption of these functions, more than the direct physical results of nuclear war, that have produced this hardscrabble world. This is not to say that there are no visible nuclear consequences. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) suggests that most fresh water is irradiated, and certainly the Wasteland is a land of mutants and stunted births. But perhaps more significant, for Miller, is the damage nuclear war has dealt to the machine of industrial civilization. Resource production, refinement, distribution; these, in the world of Mad Max, are the main casualties of societal collapse. Perhaps inspired by an Australian backdrop in which large-scale human settlement has always been a fragile imposition on an unforgiving landscape, Miller makes that fragility the major cause of his apocalypse. The machine stops spinning, and the world it once sustained is thrust beyond human reach as a result.

Some productive capacity, however, remains, and the power structures of the Wasteland are absolutely inseparable from it. Mad Max 2 sees a settlement gathered around a still-working oil refinery, its access to ‘guzzolene’ an irresistible temptation for one of the Wasteland’s roving gangs, whose vehicles are their lives. Beyond Thunderdome gives us Bartertown, whose continued economic activity depends on the energy provided by the Master and his methane-generating underground pig farm. His indispensable role in energy production (and his access to muscle of his own) mean that the Master cannot simply be ground under the heel of Bartertown’s ruler, Aunty Entity; he acts instead as a rival power center, someone Aunty Entity must bargain with or neutralize, but cannot ignore. Power is virtually never unipolar in the world of Mad Max. It orbits in complex ways around the vital resources of the Wasteland, and accrues to anyone who can enclose those resources, or the processes that create them.

The Wasteland kingdom of Immortan Joe provides an even clearer and more detailed picture of this dynamic. The Immortan himself controls the most vital resource of all, water, and with it monopolizes food production as well; but the Citadel is supplied by two other fortresses, the Bullet Farm and Gastown, and they act as fiefdoms of a sort, whose holders are close allies of Immortan Joe and wield significant influence. Dementus, though he may initially set his sights on outright conquest, settles instead for “guardianship” of Gastown, which Immortan Joe grants him in order to stave off a destructive war and add Dementus’s confederation to the protective apparatus of his kingdom (not to mention the sweetener of a crucial hostage). After all, the road between the three great Wasteland fortresses is long and dangerous, and even the Immortan’s convoys cannot travel it with impunity. Every large force he cannot enlist might threaten his crude but fundamental lines of industrial production and exchange. We might think here, as perhaps Miller and his cowriters did, of a Viking army, threatening an established kingdom with devastation, transformed into that kingdom’s nominal protectors by the grant of a duchy. Rulership means negotiation, the management of a coalition, the constant reinforcement of a power base. It is never simple, and the work is never done.

Ideological tools serve the powerful in this work, and a sampling of these tools is on offer in the Mad Max series. Immortan Joe, for instance, has built himself a kind of god-king status in the Citadel, drawing upon the mythic imagery of Earth’s past to create an army of warboys who believe they will join him in Valhalla. Aunty Entity, too, holds a powerful ideological position in the world of Bartertown: she is the lawmaker, embodying in her person a key aspect of the social order, and every time the law is invoked her right to rule is reaffirmed thereby. These tools are potent, but never sufficient in themselves. The leaders of Bartertown and the Citadel must surround themselves with skilled workers whose proximity to power is a necessary chink in the façade, figures like the Master, the Organic Mechanic, and Furiosa herself. Privileges both ideological and material are surely on offer for these lucky few. “Make yourself indispensable, and Dementus will take care of you,” advises the History Man when Furiosa is first taken captive. It is fine advice in a world where no one can rule alone.

We see this dynamic reproduce itself fractally within the great roving war-bands themselves. Mad Max 2 offers brief suggestions of smaller gangs or factions within the Humungus’s horde, and Furiosa makes this explicit in the form of the Octoboss, whose followers answer only to him, and obey Dementus only when specifically directed. There are presumably other groups like them within the confederation, who exchange some of their autonomy for the greater ambition and efficiency of the horde, or perhaps simply choose between allegiance and death. It is at the level of these individual gangs that the series begins, and we can imagine a dozen Toecutters within the ranks of Dementus’s horde, or perhaps—with a tip of the hat to Hugh Keays-Byrne’s prodigious performance—imagine the Toecutter himself building an army of his own in the scorching wastes, gang by assimilated gang. The lesson of the Octoboss, however, is that these armies are not static, these allegiances never fixed. Dementus’s callous disregard for the lives of his coalition partners robs his army of manpower and produces a new threat to the all-important shipments on the Fury Road.

Dementus’s failures of leadership are sufficiently numerous to make him a tragic figure of sorts, all the moreso given the clarity with which he sees the nature of power in the Wasteland. “The higher-ups rule only because you allow them to,” he bellows to the defeated masses of the Citadel, and we see of course that it is true, at so many levels and in so many ways; a dangerous knowledge, generally obscured by the ideologies of power. His achievement in assembling such a vast army is surely considerable, and he shares with Immortan Joe a varied and flexible toolkit for maintaining his position, incorporating fear and spectacle and the service of skilled retainers. But his attempt to better this position disrupts the fragile political economy of the Wasteland; he cannot control production in his all-important fiefdom, and by the time war breaks out it is no longer clear that he could stop it if he wanted to. In the end, his army gone, his followers dead or scattered, he faces Furiosa alone amidst the whispering sands. “I have nothing, and I am nothing,” he says, matter-of-factly, and we see again that it is true; one man alone rules nothing in the Wasteland. The machine he tried to control has stopped spinning, and the world it sustains is thrust beyond his reach as a result. So it goes.

Cinema and the History Man

The release of Fury Road saw some modest controversy over the revelation that Max had been reduced—at least arguably—to a supporting player in his own franchise film. To an extent this response was intelligible, given the dominant role of Furiosa in a narrative that bore Max’s name; to an extent also it was inevitable, given the early stirrings of what would become an unending culture war over gestures towards cinematic representation and onscreen gender parity. In the broader context of the series, however, the objection is a slightly strange one; the second and third films in the saga both explicitly position Max as a character in someone else’s story, a story lasting a lifetime or longer, in which Max played only a brief if pivotal part. Mad Max 2 is the tale of the Northern Tribe, related by their elderly leader decades after the film’s events, while Beyond Thunderdome is the story of the Lost Tribe, a group of abandoned children who ultimately find their ‘tomorrow-morrow land’. So it is with Furiosa, in whose rich and historically momentous life Max plays only a fleeting role, as many others had before him. These stories, the films insist, are being narrated, not merely depicted; and where there is narration there is always a narrator.

What it means to narrate the past is a recurring fascination of the Mad Max series, and the posited relationship between narration and truth is never a straightforward one. The black-and-white opening montage of Mad Max 2, which integrates a brief, impressionistic summary of the first film into a broader narrative of the post-industrial apocalypse, plays fast and loose with the prior ‘record’ of events; it positions Max already as a pseudo-mythic wanderer of the wastes, cast adrift by societal collapse, though we might well remember that the ‘actual’ world of the first film is, so to speak, not quite there yet. Continuity in this sense is not a major concern of the series, and Miller has suggested in interviews that each film should be taken as a legend of sorts about its central figure, connected by theme and image and character but not, perhaps, by strict chronology. There is no single story about Mad Max, but a series of campfire tales, built around a central figure who—after the brutal ‘origin myth’ of the original film—is always already complete in himself, and never quite seems to grow old.

That each of these tales has, in a sense, a different implied audience reinforces the mutability of story, its capacity to answer different questions and meet different needs. And in the world of Mad Max story is always meeting someone’s needs; out in the Wasteland after the end of the world everyone is in need of a ‘usable past’, a history they can draw upon to understand themselves and imagine their futures. Immortan Joe’s wives frame their escape from his clutches not merely in personal terms but with reference to a repeated refrain about the past: “Who broke the world?” Their understanding of the past serves to justify their pursuit of their hoped-for future, in which they are no longer ruled by men who have unmade so much. That Immortan Joe might have a rival narrative of his own, and tools for propagating it, is suggested by the onscreen role of the History Man, whose function under Dementus is to draw upon his vast reserves of knowledge only at the warlord’s command. For Miller, stories are never told in a vacuum; historical narrative can be a tool of the powerful, and even the driest recitation of ‘facts’ can serve political ends. Yet the battle for the past is never permanently lost; the History Man might work for Dementus when circumstances demand, but he can also frame the story of Furiosa, and at the end of it whisper lurid tales of a warlord humbled. ‘True’ or not, the stories we tell can liberate as well as imprison.

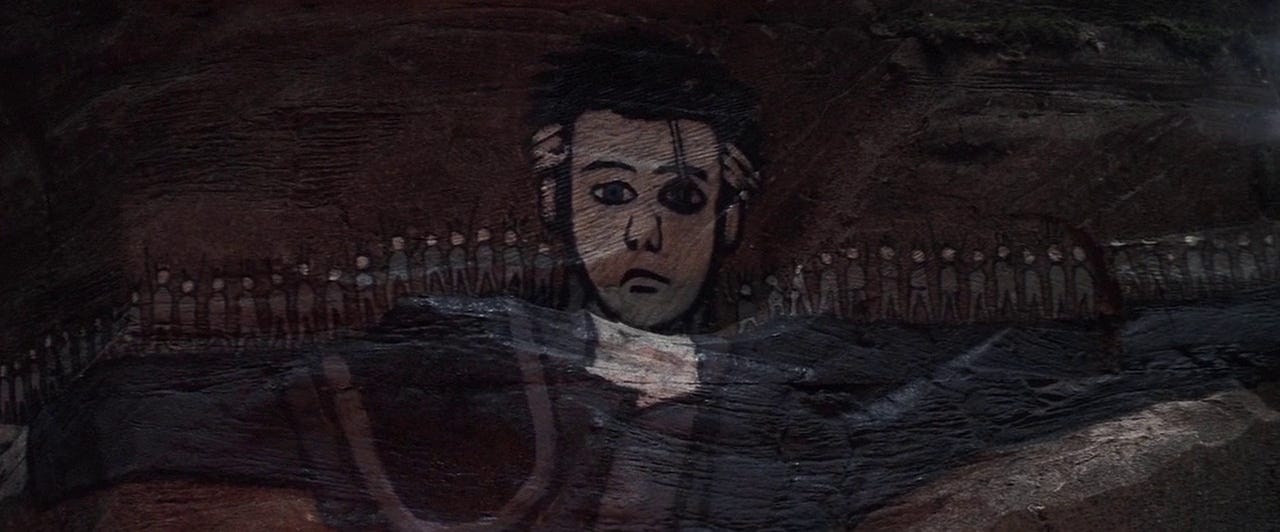

The act of narration is the subject of one of the series’ most essential and indelible sequences, which forms the centerpiece of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome’s second act. Driven from Bartertown after running afoul of Aunty Entity and her inviolable law, Max finds himself in an astonishing oasis, peopled entirely by a ‘Lost Tribe’ of children and teenagers. The survivors of a prelapsarian Boeing flight which never reached Sydney, they have been abandoned in this place—which they call Planet Erf—by adults who left in search of help and never returned. Identifying Max as their missing pilot, Captain Walker, they offer him a ritualized performance of their history called “the Tell,” reinforced by cave paintings of a sort: the crashed Boeing, the long-lost pilot, the “tomorrow-morrow land” the children never reached. As the Teller moves between images he holds up a frame, resembling the borders of a screen, making the Tell a kind of makeshift film. This fits with the children’s other fumbling yet suggestive attempts to recreate the material culture of their lost world, but the story they tell this way is the anchor of their miniature society. It gives them a shared ritual, a narrative of their common origins, and a sense of what their collective striving might bring them one day. It offers them a ‘usable past’, a history that meets their needs, a truth they can live within, and even die for.

Beyond its obvious place in the children’s broader pastiche of modernity, the cinematic frame carries another layer of potential meaning which is difficult to ignore. The film you are watching, Miller seems to suggest, tells a story just like this one; a fable that fulfills the needs of someone’s present, a tale half-remembered by someone who saw it with very different eyes. Furiosa is subtitled “A Mad Max Saga,” and there is more that makes this word suitable than its connotations of legendary scope and grandeur; the great sagas of Old Norse literature come in all shapes and sizes, but they are never free from the entanglements of politics, of collective identity, of heredity and retrospect. Cinema is burdened with all the ancient possibilities and vulnerabilities of narrative, capable of pointing towards a freer future or serving the interests of the powerful. Filmmakers and viewers will decide that together.

Scarcity rules the Wasteland; there is not enough water, not enough food, not enough fuel or bullets or healthy blood. Faced with the prospect of rebuilding an obliterated Gastown, the People Eater protests that the work will take generations; the old engines of production and the social order built atop them lie in ruins, and the work of those who survive will not see them restored in any one lifetime. Yet the conflict over those precious remaining pieces of the global industrial machine will not, for Miller, be a war of all against all. It will see instead the emergence of complex, interlocking power structures, built around the essential resources of a shattered world, and maintained by mechanisms and negotiations as old as human society itself. As in the past, so in the future.

Story, too, will follow us into the world after the end; this is, for Miller, a component of human nature as essential as they come, no less constant than the productive forces we harness or the structures of power in which we enfold them. Story will bind people back into a past that has otherwise been stripped from them, it will offer the scattered remnants of humanity a way to express the things they still share; it will bring hope in some places, and structure cruel logics of domination in others. But it will never be simple, never unitary. It will be embedded in our struggles for life and love and liberation rather than simply chronicling them, born of all the same needs that drive us to build and fuck and spill our blood. The History Man is a historical agent, and the Tell is itself a historical act; our stories will matter, as they always have, not for what they preserve but for what they do.

There is, in the end, an inescapable optimism to George Miller’s Mad Max films, as strange as it may sound to say it. He brings us a world of fire and blood, in which the work of millennia lies strewn across the desert and the lives of most are brutish and short; yet he insists that there will be life after the fall, societies, cultures, communities. Some of these will be brutal and exploitative, yes, but there will be shared struggle also, comradeship, self-sacrifice, love. In short, there will be history, the collective social enterprise of humanity, not driven to its end by the vastness of our folly but merely redirected, inscribed on a strange but exhilarating new page. The stories we tell about that enterprise will be difficult, sometimes tragic, but many—perhaps most—will be told years later in places where the promise of life has been renewed, where the Wasteland is already a memory, brushed away by leaves and grass. And as long as there are stories to tell and people to tell them, we will be alright.

Came here on Brett Devereaux’ recommendation and will stick around. Great piece.

Your essay got me to thinking about the first Mad Max movie, and I don't think I've seen it since I was a young'un. So I pulled it up on a streaming service and, wow, that's a good movie! It has a kind of "art house" feel to it (although it might be more accurate to call it a "film student" feel). It also has nods to the horror movie genre, with a few jump scares and some suspense-inducing soundtrack moments. And there were occasional moments when I suspected they were riffing on Star Wars (although maybe it's just that a young Mel Gibson looked a bit like a young Mark Hamill).

As I watched it, I really enjoyed thinking about how it was a foundational myth, as if I am an observer from the world of Furiosa, sitting around the fire and hearing the tale of the original hero, when the world was different. It really worked that way, thinking about how the latest movies draw on nascent motifs in the original — barely noticable, as if they are shadows from the ancient past. This was your essay's inspiration for me, so thank you! It really helped me understand why I like the new movies so much.